Self-compassion: Why is it important?

laura on 01/05/2024

Photo by Giulia Bertelli on Unsplash

Life can be extremely difficult. The possibility of human experience is endless. Regardless of how privileged or disadvantaged we are; human beings all connect in our capacity for psychological suffering.

We all can move to listening to a harsh internal critic. Do you have an inner critic? If so, what is the purpose of this critic? Is this critic chastising you, searching for your flaws, punishing you, and comparing you? Is it maybe even preventing you from doing things you love, or from living by your values and being your authentic self?

Let’s consider a few examples:

Imagine you have broken your leg and fractured your ribs from a bicycle accident and that you have the choice of getting help with daily tasks from companion A or companion B.

Companion A says to you: “Suck it up, it’s not that bad, you’re pathetic! Plenty of people are worse off than you, quit with the baby tears”

Companion B says to you: “This absolutely sucks. You must be in some really awful pain and feel like you’ve lost some independence that I know is so important to you. I’m here for you, let’s just take it slow together”

Strangely we are often the Companion B to our friends but often not to ourselves!

Imagine a close friend of yours just went through a romantic relationship break-up. They tell you their heartfelt story, and you listen intently from start to finish. Your friend isn’t perfect, but they deserve to be happy. You reassure them that they’ll get through this, they’re a wonderful human being, and that it can be painful, but they will be okay.

You don’t judge your friend. You don’t tell them they are not worthy, they are unlovable, will never find anybody, are ugly, stupid or that they need to change. You show your friend compassion. Strangely we often don’t do the same for ourselves!

Imagine you are at work and your boss calls you in for a meeting to have your annual review. She discusses your strengths and lets you know she is so happy to have you on the team. She then gives you some constructive advice related to organisation/planning skills. Coming from a place of critical judgment, you only hear the negative, and tell yourself, “I’m an incompetent idiot. I’m a shambolic mess and I can’t do anything right”. You head home and feel stressed out, go over all your flaws from memory and can’t sleep.

Coming from a place of fairness and acceptance, you see and hear the whole message, and tell yourself, “I’m doing a really solid job & working well with the team. I’m going to take on her helpful advice and learn from this”. This is a more compassionate response.

What is self-compassion?

There are many different definitions of self-compassion in the literature. I kind of like Neff (2003) that suggests there are 3 components that collaboratively interact to develop a self-compassionate frame of mind:

- Self-kindness versus self-judgement – Self-kindness is simply that! Responding with and developing a tendency to be caring and understanding with oneself, and letting go of the harsh judgmental critic. It is about being honest with ourselves about our pain, our flaws, our mistakes and not ignoring, and also not wallowing in self-pity; but acknowledging and responding with genuine kindness, soothing and comfort to the self.

- A sense of common humanity versus isolation – The common humanity aspect involves recognizing that all human beings have cracks, and make mistakes. We aren’t alone here! Nobody is perfect! These flaws and cracks make us who we are and connecting one’s own flawed condition to the shared human condition helps with greater perspective and understanding. Individuals who are self-compassionate accept themselves as they are and for who they are, rather than what or who they “should” be.

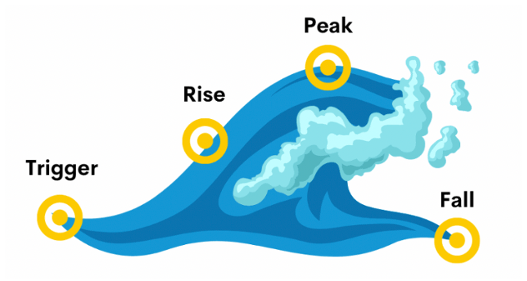

- Mindfulness versus overidentification – Mindfulness involves simply being aware of one’s present moment experience and accepting things as they are. It is not ignoring or ruminating, but observing and accepting the pain, and being self-compassionate. Mindfulness will also help in developing self-compassion habits, like recognizing when your body is feeling anxious and your thoughts are being judgmental toward yourself.

What we know from the research is that when you’re critical and judgmental of yourself, you’re more likely to experience feelings of anger, anxiety, sadness, loneliness and insecurity. When you treat yourself fairly you are in a position to manage these uncomfortable feelings with acceptance.

Self-compassionate individuals often take pride in their human characteristics and believe they are good natured, well-meaning, and competent, and happily understand their unique weaknesses or areas they can work on. They know they are a work in progress and embrace it.

It’s kind of hard to break old habits and practice self-compassion.

I encourage you to treat yourself fairly and with kindness, and see what happens.

References

Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 289-303.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and identity, 2(3), 223-250.

This blog was written by Karen Dreher – Counsellor at YMM.

Karen is a member of The Australian Counselling Association (ACA). She has completed a Masters of Counselling, a Graduate Diploma in Psychology, and additional training in Gottman (couples) Therapy.

Karen is a person-centred counsellor who values the diversity of human narrative and her client’s own personal meanings, experiences and feelings. Karen provides a warm, empathetic, authentic space that supports clients in engaging in their own self-understanding and healthy well-being.

To learn more about Karen, check out the “Our Team” page on our website! https://yourmindmatters.net.au/our-team/