The Upstairs/Downstairs Brain – Why kids have a hard time managing feelings and emotions.

laura on 17/06/2024

We have all had moments where we have felt overwhelmed and dysregulated. Swamped by big feelings and emotions, it can feel like they have control of our body, rather than the other way round. For children, this can be a particularly scary experience, and they can struggle to calm down. Teaching children about how their brains work is an important step in gaining mastery over our emotions. Knowledge is power!!

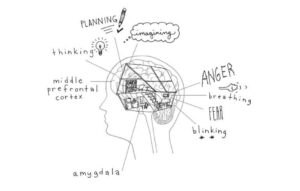

It can be helpful to think of your brain as like a house. There’s an “Upstairs” and “Downstairs” part.

Source: Image by Dan Siegel

The Downstairs part (Brainstem and Amygdala) looks after our basic survival functions. The Downstairs part is intact at birth. It is responsible for:

- Regulating breathing and heart rate

- Sensory processing

- Sensing threat

The Upstairs Part (Prefrontal Cortex) is our “thinking brain”. Fun fact parents – it’s not fully developed until you’re about 25, so it’s under construction for most of childhood and adolescence and is shaped by experience. It’s responsible for:

- Logic and reason

- Problem solving

- Making decisions and managing emotions

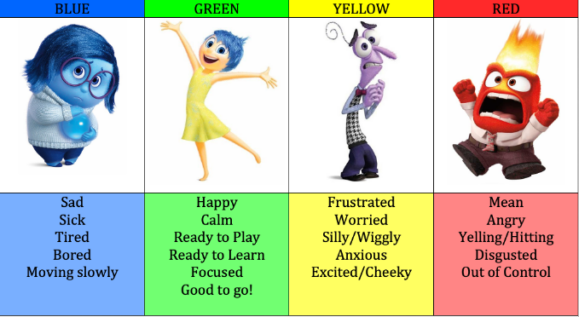

When we are calm, ready to learn, play and socialise with others, our Upstairs and Downstairs brains are communicating well. The Upstairs brain is in charge, and it can THINK before it ACTS.

But when we feel stressed, angry, or upset, our Upstairs and Downstairs brains stop communicating well. The Downstairs Brain REACTS before we THINK. When the Amygdala perceives threat, it activates a fight/flight/freeze response in the body (depending on the environment we are in and our temperament). Recent research suggests that we may utilise a fawn response as well (people pleasing). The Downstairs brain channels adrenaline, and makes us super strong, super fast and REACTIVE. This often leads children to meltdown or to become dysregulated, as they are overwhelmed by stress. In this state, it is very hard to think clearly, and it becomes the role of parents and teachers to help the child to regulate.

So, what can we do?

- Recognising signs of stress early allows us to manage our feelings, utilise strategies and regulate our emotions. In therapy, children learn to identify their emotions and associated body symptoms and develop strategies to manage stress and anxiety. Having movement breaks or moments to recharge throughout the day, and utilising strategies, can help us with managing the build-up of stress in the body and increase our coping capacity for when we do have big feelings and emotions.

- Sometimes, especially for younger children, it’s overwhelming when big feelings and emotions are triggered. If a child is dysregulated and highly stressed, the first goal is to regulate (calm heart rate and breathing, help the child to access the Upstairs Brain).

- Parents and teachers can help by:

- Keeping calm and connect! Make eye contact, move down to their level, and use a soothing tone and body language to communicate empathy. Empathic statements that reflect how a child is feeling, and NAMING the emotions/feelings they are experiencing, can help to regulate the brain and move it from a REACTIVE to a REFLECTIVE state.

- “I can see you’re feeling angry, it didn’t go the way you expected.”

- “You’re really upset that your friends hurt your feelings.”

- “You’re feeling scared at trying something new.”

- Redirecting to a calm space or activity to help soothe. A calm space such as a child’s bedroom or the trampoline can offer a space for the child to soothe and reduce sensory overwhelm. You can stay nearby and offer the child a chance to reconnect when they’re ready and feeling calmer.

- Setting safe limits to ensure everyone’s safety. Naming the feeling and setting limits on unsafe behaviour – offer viable alternatives to allow the child to express the emotion/feeling they are experiencing in a safe manner.

- “I can see you’re mad, I won’t let you hit me. You can hit the beanbag, or the cushion.”

- Keeping calm and connect! Make eye contact, move down to their level, and use a soothing tone and body language to communicate empathy. Empathic statements that reflect how a child is feeling, and NAMING the emotions/feelings they are experiencing, can help to regulate the brain and move it from a REACTIVE to a REFLECTIVE state.

Remember: You can’t pour from an empty cup!

If you are feeling stressed or dysregulated yourself, it’s okay to take a moment to step away and allow yourself space to calm down. We cannot co-regulate a child if we don’t feel calm and regulated ourselves. We want to RESPOND calmly, rather than REACT. Parenting is hard work, and it’s important to be self-compassionate.

The Power of Repair:

And once a child is calm, there’s the opportunity for REPAIR and learning. We all make mistakes and have reactive moments, even as adults. Offering your child a chance to repair the relationship, strengthens your connection and helps model healthy communication. It also helps build self-esteem and reduce the shameful feelings associated when we feel we have “messed up”.

“Hey I was wondering about how you were upset yesterday. I wonder if you were feeling this way because…….. Sometimes I feel that way too. I wonder what we could do differently next time? I love you and we can work through this together.”

Further Resources:

Dan Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson – The Whole Brain Child

https://drdansiegel.com/book/the-whole-brain-child/

Kids Want to Know – Why do we lose control of our emotions?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bKuoH8CkFc

‘If you would like to learn more about developing emotional regulation for children, or upskill as a parent in coregulation skills, our team are here to help! Call us now and take that first step towards a calmer family life.

This blog was written by Shivonne Cammell – Senior Accredited Mental Health Social Worker at YMM.

Shivonne completed her undergraduate degree in psychology and neuroscience at Monash University, followed by a Master of Social Work at University of Melbourne.

Shivonne specialises in utilising play therapy to help children recover from trauma and grief, develop resilience, enhance family relationships, and adjust to new social circumstances in positive ways. She also has experience working with adolescents and adults to address issues including anxiety, low mood and depression, low self esteem and interpersonal difficulties.

Shivonne is a warm and approachable clinician, who works from a strength-based approach incorporating methodologies including cognitive behavioural therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, interpersonal therapy, and relaxation and mindfulness strategies.

To learn more about Shivonne, check out the “Our Team” page on our website! https://yourmindmatters.net.au/our-team/